Christianity and Moral Didacticism

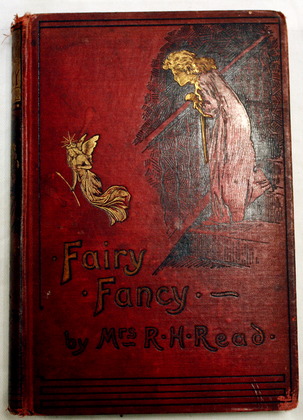

Mrs. Read’s Fairy Fancy (1883) is a perfect example of the Victorian impulse to use children’s literature to both proselytize and entertain. The Fairy Fancy of the title is less the subject of the novel than ‘what she saw and what she heard’, the moral trials, triumphs and failures of several youngster and anthropomorphic animals. The Fairy herself merely takes on the role of observer and narrator.

The novel is essentially a sequence of morality tales, revolving in some part around the villain of the piece, the raven Mephistopheles, whose namesake is the devil figure in Faustian literature. The name itself is considered by some scholars to be a combination of the Hebrew words mephiz (‘liar’) and tophel (‘destroyer’), and the children of the story ‘usually called him “Toph the thief”’ (p.11). The raven character is the embodiment of immorality, and is portrayed as the antithesis to how good children should behave. Throughout the novel he is destructive, duplicitous, murderous and cannibalistic: he entraps and kills another bird, then poses as chief mourner at its funeral exhibiting ‘no sorrow, no remorse’ (p.54). Despite his heinous actions, however, the narrator makes a distinction between his behaviour and that of the children; when watching the ill-behaved child Harry, she states that she ‘could understand Toph being fond of mischief, in fact putting evil for his good; but a boy with a soul, who knew good from evil, to choose the evil, and only think it fun, I could not understand’ (p.91). The moral adjudicator of the tale has thus passed her judgment: there is no excuse for mean-spiritedness and misbehaviour, of which the young readership should take note.

Throughout the text the narrator appeals to the audience to be righteous, disciplined and sensible in their actions; in contrast to Toph, who uses his ‘strong will’ (p.32) for evil ends, Fairy Fancy ‘assure[s] little boys and girls that they all possess it, and if they would only use their will for good it would accomplish wonders for them’ (p.32). Furthermore, when young Ella refuses to learn her words the Fairy observes ‘how much happier the child would have felt in doing right instead of wrong, for I saw she did not seem at all satisfied with herself’ (p.125). The essential theme, therefore, is concerned with both morality and discipline- young readers will flourish if they treat others kindly, and obey their elders.

There is also a distinctly Christian overtone to the novel, and mortality is dealt with in a very matter of fact way with the contrast made between a living and a dead bird which leads Ernest to ‘comprehend […] the pain and the mystery’ (p.49) of death. Once the children’s mother dies, their religious education is taken in hand by the formidable Aunt Jane who quickly gets the house in ‘Christian order’ (p.88) and begins to teach Ella the ‘catechism by rote’ (p.89). Like Fairy Fancy, Aunt Jane’s admonishments are intended as much for the reader as for the young characters: ‘”Remember, my boy, that deceit is always sure to be found out and punished in this world, as well as in the next”’ (p.121).

Thus the character of Aunt Jane literally instills the fear of God into her young charges, and by proxy the novel’s audience. Even the nativity story is manipulated to encourage discipline, incorporating a healthy dose of blackmail:

‘the poet talked to them in a simple fashion of the shepherds sitting on the plains long ago on a bright night like this, and the angel hosts coming in the sky to tell them a little child was born who would save them and all mankind, and how they went to see the baby, and how the baby grew up, and although he was wise and good, far beyond the people around him, he obeyed his mother and father in all things, and that little children should follow his example if they wanted to go to him in the beautiful house in the sky’ (p.156).