Christianity and Moral Didacticism

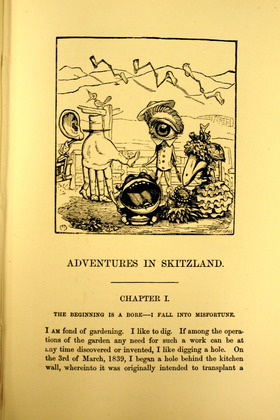

This bizarre and satirical tale was originally published in the Journal Household Words (1850), a family magazine with a mix of content for different ages and sexes. The subject matter, however, implies that Morley intended it for an adult readership. The themes are certainly mature, as well as astutely relevant to the particular period. The central conceit is as follows; the anonymous narrator of the tale digs so industriously in his vegetable patch that he creates a passage through to a parallel world, into which he tumbles. This is revealed to be the Skitzland of the title, presumably a play on the Greek word ‘schizo’ meaning ‘split’, implying that this plane is a schizophrenic reflection of the narrator’s own.

The implicit motivation of the tale is to critique and condemn the social inequality rife in Victorian England. Native Skitzlanders lose, at the age of 21, any organs or limbs which have fallen into disuse: lawyers, therefore, consist solely of tongues, and not always with brains to direct them; vain women ‘become literally dolls’ (p.46), incapable of movement but existing only to be observed; the over-indulged gentry have scalps which can be sent forth en masse to be groomed by hairdressers in preparation for fashionable events. The most vicious appraisal, however, is reserved for the aristocracy, of which the leading member is one Baron Torrero- he alone in Skitzland is a whole man, having had the luxury of wealth and an education to render all his limbs useful to him; in contrast the lower-classes who inhabit the work-houses are reduced to stomachs, filled permanently with cement so as to stave of hunger forever and allow for ceaseless labour, rendering ‘the remainder of [their] li[ves] […] forfeit to the uses of [their] country’ (p.47).

Morley’s analogy is clear, that the new breed of aristocrats of his time were the privileged capitalists who had benefitted from the Industrial Revolution. Those members of the under-class ‘who positively cannot feed and clothe [themselves and so] becomes a pauper’ (p.47) are rendered a subservient resource to provide for the upper echelons of the social strata. They are enabled to labour and nothing more, barely surviving and with no education available to them. This scathing critique of the disparity between the classes engendered by mass industry thus firmly aligns Morley with the anti-capitalist position adopted by many fairy tale writers of the Victorian period.