Christianity and Moral Didacticism

Written by the brothers Henry and Augustus Mayhew, former editors of the satirical Victorian magazine Punch, The Good Genius is a witty, if sometimes clumsy, allegorical fairy tale marketed as a Christmas book for a young readership. The essential moral of the novel is that patience and hard work are rewarded far more generously than greed and laziness, and authors’ motivation is distinctly anti-capitalist.

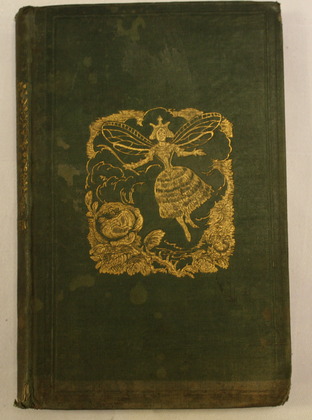

The protagonist Silvio begins the novel destitute and homeless, preferring to eat dry, stale bread over stealing honey from a bee-hive because ‘it is better to live on the crust of your own industry than on the fruits of other people’s’ (p.7). The Good Genius of the title is in fact a powerful fairy masquerading as the Queen Bee of the hive, and in return for his kindness she grants Silvio wishes based on the proviso that he maintains his attitude of humility and righteousness. Yet predictably, once the capacity for great wealth and fulfillment of every desire is made available to him, Silvio descends into idleness, complacency and greed, for which he is ultimately punished by a reduction in circumstances.

.The fairy is suitably sarcastic and sardonic so as to highlight the fallibility of man where money is concerned; the sin of materialism and the lust for ‘filthy lucre’ (p.29) are condemned outright, and the dangers of wealth transparent. The capitalist agenda is censured in the Good Genius’ story of the King and the Slave, in which gold is described as ‘the best of servants and the worst of masters’ (p.30) that ultimately ruins those who seek to accumulate it. Silvio himself, at the height of his wealth and power, is believed by his subjects to be an ‘intimate friend of another Prince, celebrated for his darkness’ (p.64). The Mayhew’s intention is clear; the acquisition of wealth at others’ expense aligns one with the devil.

Other parables which intersperse the narrative, as well as the novel’s ant-capitalist stance and fairly adult tone, Suggest that the book was intended for an adult as well as young readership. These individual morality tales, such as the parable of romance and reality (pp.38-39) and the fable of the Nightingale and the Dormouse (p.56) and their apparent divorce, seem to be intended for a mature audience. Marketed as it was for the children’s market, The Good Genius is thus an effective example of the Victorian impulse to produce work with both middle-class children and their parents in mind.