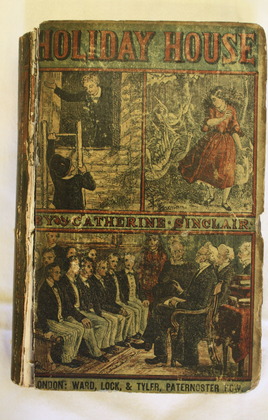

DETAILS

Title: 'Uncle David's Nonsensical Story about Giants and Fairies', in The Holiday House

Authors: Categories:Novel

Year: 1856

Location: Newcastle University: The Robinson Library, Special Collections.

Publisher: Ward, Lock and Tyler

Pagination: pp.16 (pp.346)

Dimensions: 11cm x 17cm

City: Warwick House, Paternoster Row, London.

Further Edition: 'Holiday House', (Edinburgh: W. Whyte & Co., 1839).

Further Edition: 'Holiday House', (Edinburgh: W. Whyte & Co., 1849).

Further Edition: 'Holiday House', (New York: R. Carter & Bros., 1864).

Further Edition: 'Holiday House: Tales for the Young', (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1972).

Further Edition: 'Holiday House: With a pref. for the Garland', ed. by Alison Lurie, (New York: Garland 1976).

Notes:Catherine Sinclair's first novel for children, 'Charlie Seymour: Or the Good Aunt and the Bad Aunt' (1832), adhered to the conventional Victorian approach of emphasising didactic moral instruction; her later novel 'Holiday House' (1839) however, of which 'Uncle David's Nonsensical Story about Giants and Fairies' is the central chapter, was a more developed and slightly controversial work. The novel's subjects are the mischievous youngsters Laura and Harry, who despite being essentially good-natured are constantly misbehaving; unlike the majority of child protagonists in nineteenth century children's literature, the characters are not strictly supervised or admonished to improve their behaviour, but instead advised and nurtured by their patient guardians Grandma Harriet and Uncle David. Uncle David’s story represents what Sinclair considered the most effective approach to educating children; instead of suppressing their creativity and controlling their behaviour through discipline, they should be encouraged to use their imagination to develop autonomous moral judgement. Uncle David’s story is one of the few moments in the book which ‘provides an example of moderation’ (Zipes, Victorian Fairy Tales, p.1.) for Harry and Laura, and yet it is the most fantastical passage. Sinclair strongly believed that the mechanisation of the urban experience engendered by the Industrial Revolution, the administering of rigid discipline and a Victorian educational ethic that eschewed idiosyncrasy and creativity was detrimental to young minds; she states her case adeptly in the preface to ‘Holiday House’: ‘In this age of wonderful inventions, the very mind of youth seems in danger of becoming a machine; and while every effort is used to stuff the memory like a cricket-ball, with well-known facts and ready-made opinions, no room is left for the vigour of natural feeling, the glow of natural genius, and the ardour of natural enthusiasm.’ (p.vi)